Transocean ($RIG)- Buying Offshore Rigs for 30 Cents on the Dollar

A long duration value opportunity to buy the leading company in a sector undergoing a historic demand inflection

Quick note: due to the longer length of this post and the number of charts and images, I would recommend reading directly through the Substack website instead of by email.

“The stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient.” — Warren Buffett

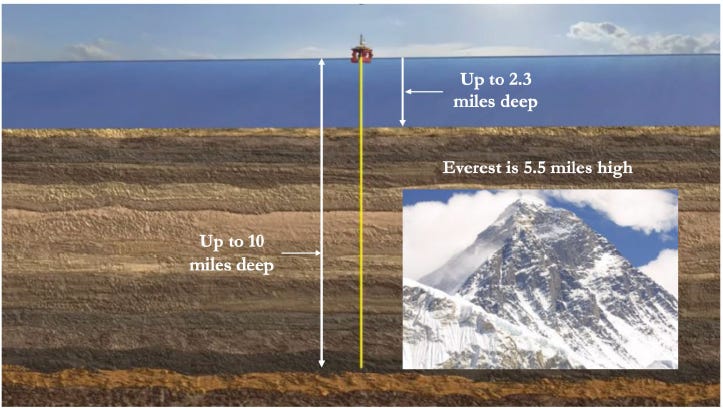

Let’s start with a quick mental picture. Imagine a ship that is 2 football fields long, one football field wide, and weighs more than an aircraft carrier. The ship has a thrust capacity rivaling that of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and can drill in 12,000 feet of water (~2.3 miles), and a further 40,000 feet (~7.5 miles) into the earth’s crust, for a total drilling depth of 52,000 feet (~10 miles).

To put this into perspective, the Empire State Building stands 1,454 feet tall, counting the spire and antenna. That’s a drilling depth equivalent to almost 36 Empire State Buildings stacked on top of one another.

Here’s another reference point — Mount Everest, the highest point on Earth, is about 29,000 feet (or 5.5 miles) tall. So this same ship can drill down to a vertical depth that is almost twice the height of Mount Everest.

Now picture a row of 26 such ships lined up next to each other. In addition, visualize another 11 giant, football field-sized marine vessels with somewhat similar drilling capabilities right next to the 26 ships, for a total of 37 vessels of stupefying scale.

As you’ve probably surmised, what I’m describing to you is indeed Transocean’s fleet of 26 drillships and 11 semi-submersible rigs. At a high level, Transocean (“RIG”) owns and manages these offshore drilling vessels, and provides contract drilling services to global energy companies such as Exxon Mobil, Chevron, and Shell. These oil majors in turn typically lease the drilling rights to the oil and gas buried deep underneath the seafloor from governments of countries such as the US, Brazil, and Norway.

Given that RIG owns 37 vessels (technically it partially owns 2 of the vessels), in trying to figure out what the company is worth, the simple napkin math may be to first estimate what it would cost to replace RIG’s whole fleet. A brand new drillship ordered today is estimated to cost ~$1 to 1.2 billion, while a high-specification semi-submersible would likely cost a bit more. Using the low end of the range for conservative purposes, the fleet’s replacement value would be ~$37 billion ($1B x 37 vessels).

Although a crude approximation, with this in mind, here’s a quick snapshot of some high-level metrics for RIG’s current market valuation and earnings power:

Without going into further detail, it’s apparent that there may be some interesting value here. With a total enterprise value of roughly $10.7 billion ($4.3 billion of market equity and $6.4 billion of net debt), RIG is trading at a significant discount to our estimated replacement value — roughly 70% discount assuming a $37 billion replacement value. Given the big value disparity, the natural question arises: is there truly a large gap to intrinsic value and, if so, why does it exist?

What’s the Market Missing?

In my judgment, RIG is significantly undervalued. For those that have read my post on Tidewater, much of the following discussion is going to sound very familiar. Back in December of 2022, I laid out my thesis on Tidewater, and on the offshore energy space in general, as I believed that the company was on the cusp of a crucial positive inflection in earnings due to the underlying demand-supply fundamentals. Since then, my thesis has played out faster than I had expected — Tidewater’s stock has appreciated ~3x in just over a year from ~$30 per share to ~$90 per share, compared to my original expectation of 2-3x return over a 2 to 3 year horizon.

Although I still own and continue to hold my stake in Tidewater, as we sit here today in March of 2024, I believe Mr. Market is offering us another bite of the apple in the offshore drilling sector through companies like Transocean ($RIG), Valaris ($VAL), Noble ($NE), Seadrill ($SDRL), and Diamond Offshore ($DO). Like Tidewater, based on current valuation levels, RIG offers a highly asymmetric risk-return profile and, in many important ways, may provide an even more attractive investment opportunity, especially from a long-term duration standpoint.

So what’s the market missing? I think there are a few contributing factors. The first big one is heightened investor myopia. In general, when it comes to public markets, especially stocks, most investors are focused on anywhere from the next quarter to 18 months into the future. For the retail crowd, the horizons are likely even shorter with the proliferation of Robinhood, 0DTE options trading, meme stocks, and the recent euphoria in AI, NVIDIA, and crypto.

As a consequence, companies that require a little bit more patience for outstanding returns like Transocean end up being tossed aside as they take too long to play out — even though they may only need an extra 6 months or a year beyond the 18-month threshold. This idea that potential equity returns increase significantly beyond a 2-3 year horizon was first introduced by Horizon Kinetics in the early 1990s as the concept of the equity yield curve, and is a key guiding framework in my investment philosophy.

A second major factor contributing to the value gap is the continued investor apathy for the energy sector at large, and the offshore services sector in particular. ESG mandates have played a critical role in diverting large pools of capital away from the sector but another key element at play is the highly cyclical nature of the sector — many investors lost a ton of money over the past decade in the energy sector and are hesitant to return.

In the case of the offshore drilling sector, the pain has been especially severe. During the 2016 through 2022 period, virtually every major offshore drilling company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy except for one company: Transocean. Although long-term stockholders of Transocean weren’t wiped out in bankruptcy, they might as well have been given the stock price performance over the past decade:

A third element that the market may be missing, and one more specific to RIG, is the underlying concern over the company’s heavy debt burden. The reason why RIG has such a high level of debt, relative to its current earnings and its industry peers, is because it is the only company in the sector to have avoided bankruptcy. As a result, it still carries a lot of legacy debt that helped finance asset acquisitions during the past cycle. Although a high debt load often increases risk in an investment, I believe the concern here has been largely overblown for a number of reasons.

First, the debt figure is high but it’s not as high as it looks. On a TTM basis, RIG is trading at a net debt to EBITDA leverage ratio of ~9.7x, certainly an alarming figure at first glance. However, through a combination of inflecting earnings (discussed later in this post) and debt paydown from future cash flow, I expect this ratio to decrease to a more reasonable range of ~5x by the end of 2024 and to less than 2x by the end of 2026 (assuming no refinancing).

Secondly, it is also silly for some observers to argue that Transocean is insolvent. Nothing can be further from the truth. With the upcycle in offshore well underway, capital markets have reopened for the sector, especially for disciplined, well-managed players such as Transocean. As evidence, one simply needs to look no further than the financing transactions accomplished in just the past year:

Extended the $600M revolving credit facility to mid 2025

Refinanced $1.175B of secured notes with an improved amortization profile due 2030

Secured a $525M financing on the newbuild drillship Deepwater Titan due 2028

Secured a $325M financing on the newbuild drillship Deepwater Aquila due 2028

Clearly, an insolvent company wouldn’t be able to persuade its creditors to refinance existing loans, let alone secure new loans at fairly attractive rates (~8 to 8.5%).

Investment Thesis

There are 5 key prongs to the thesis for Transocean:

The world needs ultra-deepwater oil and gas

There’s a looming shortage of deepwater rigs

The offshore drilling sector has evolved into an attractive oligopoly

Buying quality at a fraction of replacement cost

Management matters

1) The world needs ultra-deepwater oil and gas

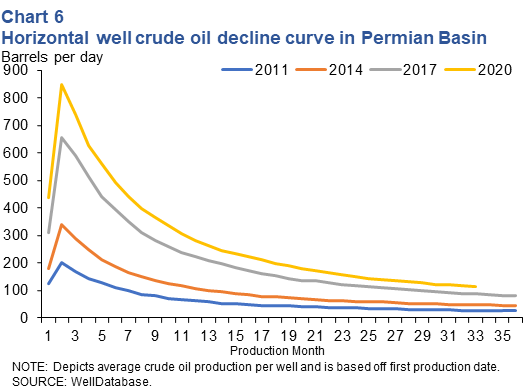

Ever since the oil market collapse in 2014, we’ve been severely underinvested in oil and gas (“O&G”). I’ve discussed this issue numerous times in the past but to restate the observation at a high level, the world has been consuming more oil than it has been discovering. The natural consequence is that at some point in the future, we’re going to find ourselves in a crucial deficit as old wells begin to dry up and the production from new well discoveries become insufficient to meet global demand. One simply needs to look at the historical data. To help illustrate my point, here are a few useful charts:

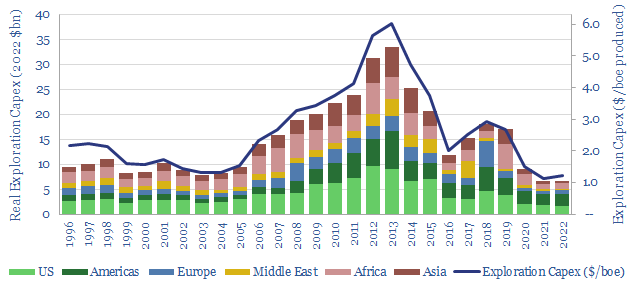

As you can see based on the chart above, prior to the collapse in 2014-2015, total global exploration and production (“E&P”) CapEx peaked at ~$800B before plunging in half to ~$400B. Between 2016 and 2019, as the industry was just starting to recover and invest in the search for new reserves, COVID led to another collapse and effectively delayed critical investment for another 2-3 years.

In this chart, we have historical E&P CapEx depicted for five Oil Majors: Exxon Mobil, Chevron, BP, Shell and Total. The additional layer that we have here is on a $ per boe produced basis: CapEx declined from ~$5.8 per boe down to ~$1 per boe, a whopping decline of 83%. In other words, the major E&Ps have been drawing down heavily on their old inventory and have not been adequately replacing their inventory for future growth.

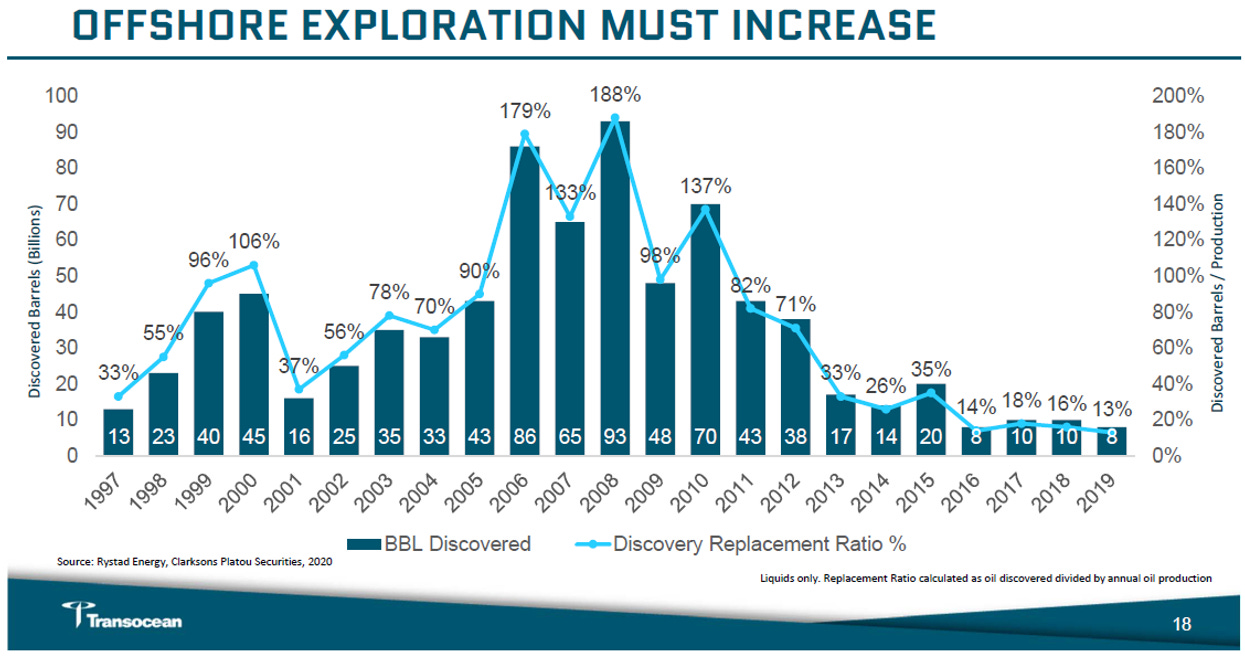

This next chart shows the exploration trends from an offshore perspective. As you can see, from 2002 to 2012, we had very robust exploration activity in the offshore space with record years in 2006 and 2008. In 2010, we had the historic Deepwater Horizon or BP oil spill, which prompted the significant decline in activity in the ensuing years. Since the collapse of oil prices in 2014-2016, offshore replacement ratios have persistently stayed below 20%, and likely declined even further during the COVID years of 2020 and 2021. So we’ve had well below average discovery replacement activity for the better part of a decade.

Meanwhile, global liquid fuels consumption has recovered back to pre-COVID levels and is projected to continue to increase for the foreseeable future. The inexorable truth is the world will require significantly more oil and gas, not only to support the achieve the ambitious renewable energy targets but also to meet the escalating demand from Asia and Africa as they strive to improve their standards of living.

Now that we’ve established the need for increased O&G exploration, where are the incremental barrels going to come from? The short answer is anywhere that we can find it — both onshore and offshore. However, it’s plausible that we’ve largely discovered all the major onshore basins at this point. Although the opportunity set for onshore production remains attractive, especially in prolific regions like the Permian Basin, offshore presents a compelling alternative to narrow the potential supply gap in the future.

The underlying reality is that over the past decade, due to huge advancements in offshore drilling technology and processes, the economics for offshore production, especially ultra-deepwater, have become a lot more attractive for a few key reasons:

Lower breakevens: average breakeven cost of production for offshore has decreased by ~50% from $64 per barrel in 2016 to ~$34 per barrel in 2020, making it very competitive relative to onshore shale production and other sources of oil supply.

Lower CO2 emissions intensity: offshore deepwater offers the lowest average CO2 intensity per barrel of oil produced among all sources of oil supply. This attribute is appealing for E&Ps as they are increasingly pressured to reduce emissions given the focus on ESG and climate change mandates.

Lower decline rates, larger potential reserves and production rates: offshore’s massive resource potential and high production rates make it indispensable in our quest to plug the potential oil supply gap in the future. Just to give you a better sense:

The initial production rate of some of the best wells in the Permian Basin is generally over 1,000 barrels of oil equivalent (boe) per day for the first few months and then it rapidly declines down to roughly 300-400 boe per day by the end of the first year. After that, the decline rate slowly flatlines over the remainder of the well’s life, which can be anywhere from 10 to 50 years.

Production rates for shale wells peak within the first 3-4 months and then rapidly decline to 1/3 of peak by the end of the first year | Source: Dallas Fed On the other hand, the typical average offshore well can easily produce anywhere from 10,000 to more than 20,000 boe per day, an order of magnitude greater than the average Permian well, and the production declines a lot more gradually than a typical onshore well due to the nature of the geological formations and vast reserves.

And within offshore, a reason to focus on the deepwater and ultra-deepwater segment of the market is that it is expected to experience higher growth in CapEx relative to the shallow water (shelf) segment. As a note, the market is also typically segmented by rig type including floaters, which include drillships and semi-submersibles, and jackups. Floaters service deepwater projects while jackups service shallow water projects.

It’s also worth highlighting that the two key demand drivers for the offshore services sector are medium to long-term oil price expectations and offshore upstream CapEx. The relationship between the two variables is intuitive: as expectations for oil prices rise, oil companies boost offshore CapEx to find new oil. This increase in CapEx in turn fuels demand across the entire offshore services industry, including marine geophysical surveying companies, engineering and construction firms, offshore support vessel (OSV) and offshore drilling companies.

In addition, the reason why sector performance is driven by medium to long-term oil prices, as opposed to short term oil prices, is because the sector is long cycle in nature. Projects often require billions of capital and many years to develop which, as we’ll see in thesis point #2, leads to amplified effects on demand and supply of rigs from a capital cycle perspective.

2) There’s a looming shortage of deepwater rigs

Now that we’ve established that demand for offshore rigs is growing, let’s touch on the supply side of the picture. We'll primarily focus on the floater rig market as Transocean does not own any jackup rigs.

To provide a bit of context, let’s revisit how supply has evolved throughout the past cycle. During the bull period in oil from 2002 to 2014, supply grew rapidly in the offshore space as operators expanded capacity to capture the ever-growing demand for oil. With strong growth in E&P CapEx fueled by rising oil prices, offshore drillers spent billions on constantly renewing and constructing new vessels to grow their fleets, unperturbed by the potential oversupply that would result if the tides turned.

In classic fashion of boom bust cycles, the undisciplined supply growth led to a large imbalance once the bear market arrived in 2014-2016. Following the price collapse in oil, major oil companies slashed offshore CapEx budgets as projects became less profitable. Many companies diverted capital to other sources of production such as onshore shale in the Permian Basin, where breakevens were lower and payback periods were measured in months not years.

The resulting pain for the offshore drillers was further exacerbated for a few reasons. First, the supply response was delayed because the delivery lead times for newbuild vessels were long (typically 18 to 24 months). So despite declining demand, new rigs continued to be delivered in 2016-2017, amplifying the supply imbalance.

Second, the high operating leverage nature of offshore drillers began to work in reverse. As operating day rates and utilization declined, profits cratered. It’s very costly to operate an offshore drilling vessel — depending on the region, a typical drillship can cost anywhere from $130-140k per day to operate, while a harsh environment semi-submersible rig based in a high-cost jurisdiction like Norway can cost upwards of $160-180k per rig. So with day rates plummeting from ~$600k per day to less than $200k per day, and active utilization rates declining from over 90% down to ~50%, drillers found themselves hemorrhaging cash and struggling for survival.

To protect their balance sheets, many drillers were forced to either cold-stack their rigs (reducing the crew to zero or just a few key individuals and storing/maintaining the rig in an environment such as a harbor or shipyard to keep the vessel in good condition) or scrap older rigs altogether.

Fast forward to 2019, just as the industry started to show signs of recovery, COVID delivered another crushing blow, plunging the entire sector back into a tailspin in 2020. The ensuing collapse was the final nail in the coffin for many major players — Valaris, Noble, Diamond Offshore, and Seadrill all went into bankruptcy. As a result, a wave of consolidation and supply rationalization followed to bring the market back into balance.

Fortunately, with the passing of COVID and increase in CapEx / demand for offshore, the sector has resumed its recovery momentum. In fact, in the past two short years, day rates have more than doubled from less than ~$200k per day to now close to ~500k per day as accelerating demand vacuumed up the reduced supply. Many regions such as the US Gulf of Mexico, Norway, and Brazil are now effectively sold out (100% market utilization) and are even pulling available rigs from other regions of the world.

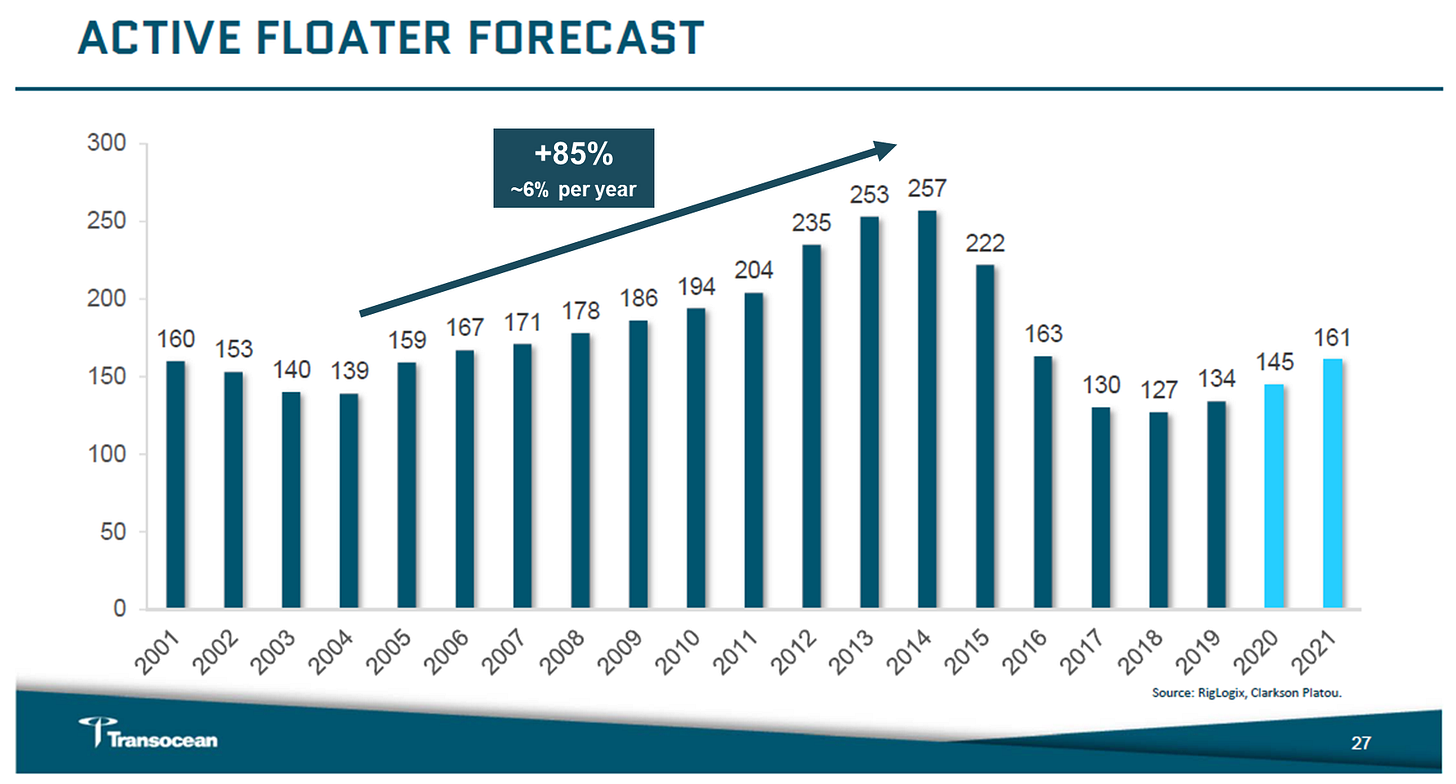

So what does rig supply look like now? These numbers are not precise down to the single digits but at a high level, we’ve made a full round trip — we started with ~150 floater rigs in 2004, ordered a total of ~184 rigs between 2004 and 2014, bringing the total active and newbuild supply to a peak of 334 rigs, and then scrapped almost an equivalent amount between 2014 and 2022 to bring the total back down to 150.

More importantly, there are several crucial elements that serve to keep a lid on the growth in rig supply for the foreseeable future. Although day rates have recovered meaningfully, they’re still below prior peak levels of ~$600k per day, and well below day rates needed to incentivize newbuilds. Assuming $1 billion newbuild costs, rates would have to rise to ~$800k per day and be expected to sustain at such elevated levels for a reasonable period of time for drillers to make an adequate return on newly built rigs (see graphic below).

A general rule of thumb for newbuild economics used by the industry is you need a $1,000 dayrate for every $1 million of build costs. So if a newbuild drillship costs $1 billion, you would need $1 million day rates to justify the cost.

As evidenced by the chart above, the orderbook (i.e., current orders for newbuild rigs) peaked at a staggering 45% of the total fleet in 2009 before declining to ~20-25% of the total fleet in 2014 and ~12% currently. The majority of current orders are actually stranded newbuilds owned by shipyards that were ordered in the prior cycle but canceled by offshore drillers following the 2014-2015 bust. Adjusted for competitive rigs, the orderbook is even lower at 5%. In other words, there’s virtually no new supply on the horizon.

Speaking of shipyards, another crucial factor that will prevent new supply is shipyard capacity and their low willingness to build new offshore rigs. Shipyards suffered significant losses in the last cycle because 1) many offshore drillers canceled or defaulted on their newbuild orders and 2) contracts had extremely customer-friendly payment terms (upfront payments were as low as 10% to begin construction).

Many shipyards in China and Korea were forced to liquidate and had to lay off hundreds of thousands of employees. Many yards ended up retooling their assembly lines to service strong demand for other types of marine vessels like LNG carriers and cargo ships. The newbuild infrastructure has been dismantled — it will take many years to restaff the ecosystem and rebuild assembly lines to build offshore rigs once again.

Insights from expert calls and industry experts have also confirmed the limited desire of Korean shipyards to support a revival of newbuild orders for offshore rigs. As a starting point, any newbuild orders in this cycle will likely require an upfront payment of as much as 40% to even begin construction. And in terms of timeline, Transocean management has noted on past earnings calls that a new offshore drilling vessel ordered today would take at least 3 to 5 years to deliver, if not longer for higher-specification vessels.

Lastly, management teams are also hesitant to order new rigs due to the risk of owning a stranded asset. After all, offshore rigs have a long useful life of at least 30 years while ESG mandates and climate change goals are targeting net zero by 2050. Anyone ordering a new rig today would have to make the bold assumption that oil would continue to stay critical to the global energy mix in 2060 and beyond and that offshore production does not get supplanted by cheaper sources of oil. Although such an assumption is likely correct, few management teams would be willing to make that bet anytime soon, especially where day rates are currently.

Given this backdrop, I’m optimistic that the rig supply picture will remain favorable for at least until the end of this decade.

3) The offshore drilling sector has evolved into an attractive oligopoly

The offshore oil and gas industry has a long and interesting history dating all the way back to 1896, when the first oil wells were drilled from wooden piers connected to the shores of Summerland, CA. I won’t dive into the full history for the sake of the length of this post but for those that are interested in getting a deeper overview, I would highly recommend reading Chapter 2 of the Report to the President by the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, which you can access through this link.

Given that the industry has been around for almost 130 years, there have been many waves of consolidation as part of the constant boom and bust cycles. Tracing Transocean’s history alone reveals that the company is a product of a long list of 13 predecessor companies, each a result of earlier mergers and spinoffs.

Through this evolutionary process, the offshore drilling industry has now rationalized to a point where the top 5 firms control over 70% of the currently operating floaters. Not only that, further consolidation is also likely in the short to medium term as operators continue to look for ways to join forces and grow their fleet accretively (especially given current depressed values).

This level of concentration is paving the way for much greater pricing power going forward as each player has increased negotiating leverage with the big oil companies. When we combine this dynamic with the tightening supply trends described previously, we should expect to see very favorable outcomes for future operating margins and returns on capital for the sector.

With regard to pricing power, my friend Nick Radice (@NickRadical4 on Twitter), a very shrewd value investor, drew interesting parallels between the offshore drilling industry and the railroad industry. He observed that for most of its history, the railroad industry was also deeply cyclical and generated meager returns for investors due to its high capital intensity and fierce competition. However, once the industry matured and consolidated into just a handful of players, the resulting pricing power enabled the whole sector to generate much higher profit margins and returns on capital. That’s why Bill Gates loaded up on Canadian National Railway ($CNI) back in 2000 and why Buffett ended up acquiring BNSF in 2010. This dynamic would be the path to a 20x to 30x outcome over the next 10-15 years if it play out as expected.

"The single-most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power. If you've got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you've got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price by a tenth of a cent, then you've got a terrible business. I've been in both, and I know the difference." — Warren Buffett

4) Buying quality at a fraction of replacement cost

Out of the 5 thesis points, this one is likely the most impactful driver of ultimate returns. When you buy hard assets at a 70% discount to replacement value, not much has to go right to end up with a favorable outcome. And when you tack on the fact that the assets are appreciating in value due to increasing scarcity and accelerating demand, it becomes pretty difficult to lose money provided that you have the appropriate investment horizon. Given the long cycle nature, I would argue that the horizon needs to be at least 3 years, if not 5 years or more.

Although the whole sector is attractive, there are a few important nuances that sets RIG apart from the rest of the players. First, RIG unquestionably owns the highest specification fleet in the industry. It’s the only player with the two newest, most technically capable eighth-generation drillships that were delivered in 2022 and 2023. These best-in-class drillships are the only assets in the market with a 1,700 short ton (3.4 million lbs) hoisting system and a 20,000 psi blowout preventer (20K BOP) system.

Put simply, the 1,700 ST hoisting system allows the customers to utilize fewer casings strings, reduce trips downhole, and preserve a larger borehole for follow-on production activities — all of which increases drilling efficiency by shortening well drilling time. When every day of operation can cost an oil company over a million dollars, having the technology to potentially shave off a few days in a drilling program can be very valuable.

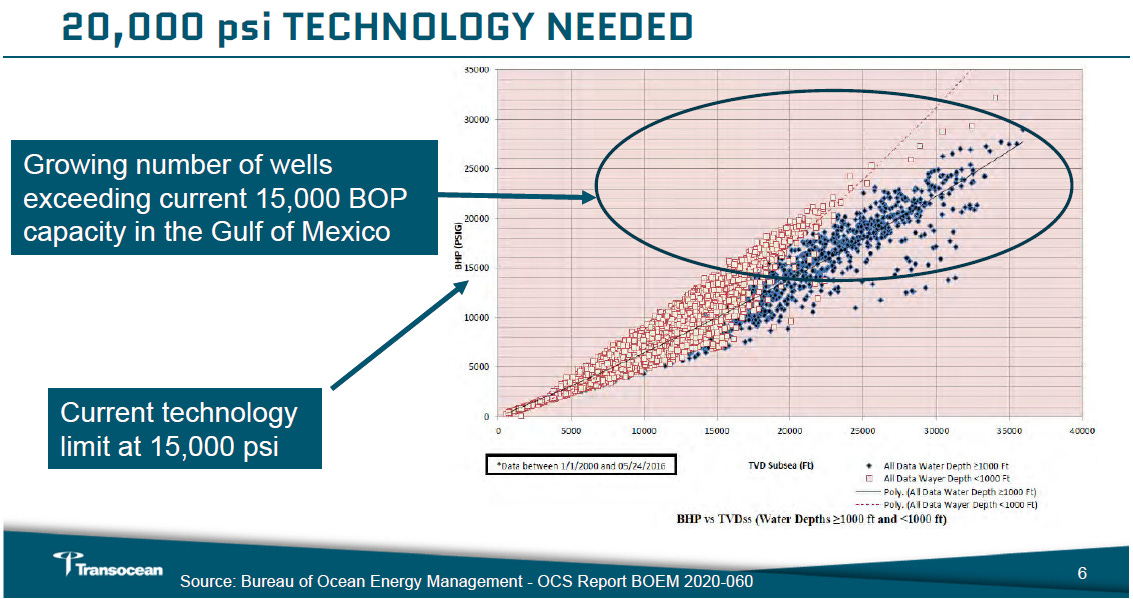

The 20K BOP system is an even more important technological innovation for the industry. The new technology unlocks a wide set of projects in the US Gulf of Mexico that were previously infeasible due to the higher pressure and higher temperature environments in the deeper reservoirs.

This first-mover advantage in technology and operating experience should not be overlooked. As the only pure play operator in the floater segment of the offshore space, RIG has cemented its reputation as the undisputed technical leader for ultra-deepwater operations. Throughout their history, Transocean’s legacy companies achieved many industry-firsts such as building the first mobile jackup rig and the first drillship (both in the 1950s), the first semi-submersible rig (1960s), pioneering the dynamic positioning (DP) technology in 1970s, and constructing the first ultra-deepwater dual activity drillship.

During the downcycle, management also pursued a deliberate strategy to hone in on the ultra-deepwater (UDW) and harsh environment (HE) segments — they completely transformed the fleet and divested all the midwater and shallow water segment assets. They believed that in the long-term, their reputation, operating experience, and technical superiority in the UDW and HE segments would be crucial in differentiating them from their competitors. They also shrewdly recognized that these segments had much higher barriers-to-entry relative to the shallow water jack ups and midwater segments, and that UDW and HE presented higher growth and longer duration opportunities in the long-term.

Lastly, RIG has the most operating leverage out of all the offshore drillers. Given newbuild supply is virtually non-existent, and will likely stay that way for at least the next 5-7 years, the incremental supply will have to either come from reactivation of cold-stacked vessels or delivery of stranded newbuilds owned by shipyards. Per the February 2024 Investor Presentation shown above, RIG owns 8 of the 17 stacked drillships currently, giving it the greatest capability to grow earnings and capitalize on the accelerating offshore upcycle.

5) Management matters

The last key aspect to the thesis that hasn’t been given nearly enough attention is the quality of RIG’s management. In a business that is as deeply complex and technically challenging as offshore drilling, operating experience and expertise matter. Relationships matter. When there’s so much at stake, as a customer, you don’t want the lowest price. You want a partner with the most experience to get the job done right the first time, and have it done in a timely fashion. The barriers to entry for a new entrant are insurmountably high.

It’s no accident that RIG was the only company to stave off bankruptcy in the last downcycle. Although there was some element of luck, such as their fortuitous timing in locking in 10-year contracts on 5 newbuild assets at peak day rates (~$500k+) before the collapse in 2016, factors such as their disciplined contracting philosophy and brand reputation are much less up to chance.

There’s a reason why 1) Transocean consistently has the largest revenue backlog in the industry, 2) why many customers have approached Transocean directly for contract negotiations in the past several years, as opposed to casting a wide public tender for everyone to bid on, 3) why the company often secures leading-edge day rate contracts with more favorable terms, and 4) why they’ve been one of the very few operators to link compensation with operating performance. It’s because they stand behind their operational excellence and are confident in their ability to deliver value for their customers.

“We have some of our customers telling us we know that you guys are a bit more expensive. You perhaps deserve that premium.” – Transocean management comments relaying customer feedback, July 2020

All these elements are self-reinforcing and could be thought of in this positive feedback loop:

Valuation

With respect to valuation, the math is simple. On a statistical basis, RIG and all the major offshore drillers are trading at attractive levels on both a balance sheet perspective (historical cost or replacement cost) and future earnings perspective. Here’s a high-level overview of the relevant ratios for the top 5 players:

At first glance, you’ll note a few interesting observations. First, due to Chapter 11 bankruptcy restructuring, virtually all the drillers have very limited net debt, except for RIG. In addition, the EV to PP&E figures for RIG’s peers are not meaningful as the legacy equity value used to acquire the assets had been extinguished, lowering the PP&E and book equity values. Overall, there’s very limited balance sheet risk besides RIG and we’ve covered earlier why there shouldn’t be much concern for RIG’s leverage either.

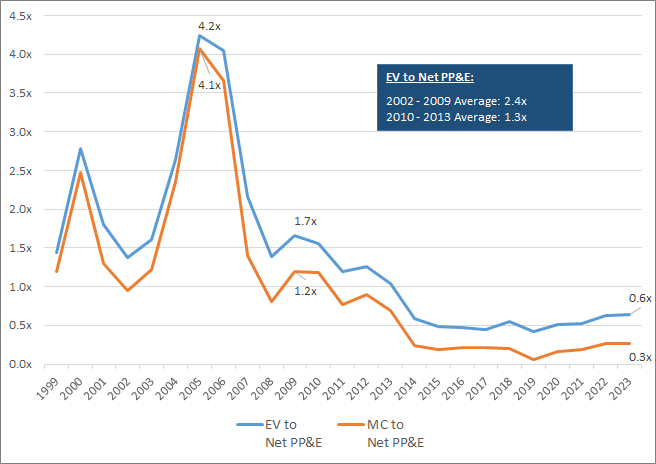

However, when we look at RIG’s EV to PP&E ratios, we see that the company is currently trading at roughly half the historical gross PP&E cost or 0.7x net PP&E (after depreciation). What have these ratios looked like historically?

Based on the graph above, we can see that the current EV to net PP&E ratio is well below the historical averages. If we look at the average during the last upcycle between 2002 and 2009, the ratio was 2.4x, or 1.8x if we exclude the seemingly outlier figures in 2005 and 2006 where the ratio spiked to over 4x. Even in the 2010 through 2013 period following the Deepwater Horizon disaster, the ratio was still higher than current levels at 1.3x EV to net PP&E. So looking at these balance sheet ratios alone, we can see that if there was simply a reversion to the mean, Transocean is at least a 2 to 3x return opportunity.

Turning to earnings, we find a similarly positive picture. Based on the comps analysis table above, the median EV to 2026 EBITDA for the group is 4.5x or conversely, a ~22% EBITDA earnings yield. Although 20%+ is a fairly respectable yield, I expect this figure to exceed 30% as we extend the horizon beyond 5 years when day rates approach $600k - $700k per day.

That being said, we don’t need $600k dayrates to achieve a favorable investment outcome. Even at current high $400k to 500k day rate levels, Transocean is already generating meaningful cash flow to deleverage the balance sheet. Even if Transocean’s enterprise value stays constant over the next 5 years, the process of deleveraging the balance sheet alone should provide a high-teens return as the equity value accrues a larger share of the total EV pie.

The key revenue drivers for offshore drillers are fleet utilization, which is driven by active rig count, and contracted day rates. For dayrates, given that Transocean has locked in multi-year contracts for many of their vessels, I’ve assumed for the base case scenario a fairly conservative UDW fleetwide average increase to $480k per day by YE 2026 (Year 3) and $550k per day by YE 2028 (Year 5). Similarly, the HE fleet is also assumed to follow a similar trajectory with a slight day rate premium to the UDW drillships.

With regard to utilization, on the UDW side, I’ve assumed that out of the 12 currently idle/stacked rigs (10 stacked, 2 idle), the 2 idle rigs will be fully active by 2025 and that RIG will be able to bring 2 cold-stacked rigs online by the beginning of 2027 and 1 additional rig by 2028. For the HE segment, I’m assuming that Henry Goodrich remains stacked for the foreseeable future given its old vintage. Using these assumptions, here are what my return expectations look like based on my average cost basis of $5.31 per share:

Based on this rough cash flow model, we can see that the expected 3-year and 5-year IRRs are over 30% for the base case scenario using a 6x EV/EBITDA exit multiple. For context, the 6x exit multiple is also not heroic – RIG averaged over 15x leading up to the GFC and ~7x in 2013 before the oil bust, despite the overhang from the Deepwater Horizon incident.

Risks

It goes without saying that with every investment, there is always some risk that one needs to bear to realize the outsized returns. In the case of Transocean and the offshore drillers, I think the biggest risk by far is the risk of a major oil spill like Deepwater Horizon in 2010. Although this risk is intrinsic to the business and will never go away, significant advancements in drilling technology and safety processes have helped mitigate the possibility of another catastrophic event to a great extent. The only way to manage against this risk from a portfolio perspective is to size the exposure prudently.

The other key risk of course is the underlying uncertainty in the global demand and supply of oil, which in turn drives medium to long-term oil price expectations and offshore CapEx. There is always an inherent risk that we may somehow find ourselves in an oil supply glut due to a massive oil discovery in some dark corner of the world or that OPEC’s spare capacity is actually greater than what everyone thought, or maybe that onshore Permian shale production revamps again. Although no one is smart enough to accurately predict the future of oil, based on our observations of the past, the probability of any of these scenarios materializing is likely to be remote.

Closing Thoughts

Per the opening quote to this post, this thesis will take time to play out. Investing in the energy sector always involves a lot of volatility and can be an advantage for the opportunists or a nightmare for the faint of heart. Although I’ve chosen to highlight Transocean as another way to bet on the offshore thesis, I believe a prudent approach would be to own a diversified basket of the top 5 players in the space as such an approach would capture the sector beta and hedge against the idiosyncratic risk of any one company. Many prominent and savvy investors in the sector have picked Valaris and Noble as their way of exposure instead of Transocean due to the lower balance sheet risk and additional diversification in the shallow water/jackups market. My personal preference has been to concentrate on Transocean and Tidewater, but I may decide to expand my offshore basket to include some of the other players as well.

Disclosure

I am long Transocean ($RIG). As always, this is not investment advice. Please do your own DD before investing.

Great article Tuan!

I think you’d laid out the thesis well with a few key points that are hardly mentioned from the NE and VAL camps:

1) RIG’s backlog continues to grow. They’re highly desired by their customers.

2) Superior management. Companies are willing to pay a little more for their service. That’s what also attracted me to RIG instead of the other two.

The Valaris warrants are worth a look if you want some torque on that one. Basically a super long dated call option on an offshore bull market.